In the last month, actions by the courts, the President, and Congress have significantly impacted and may further change how Title IX is enforced across the country.

Title IX: Background and Enforcement

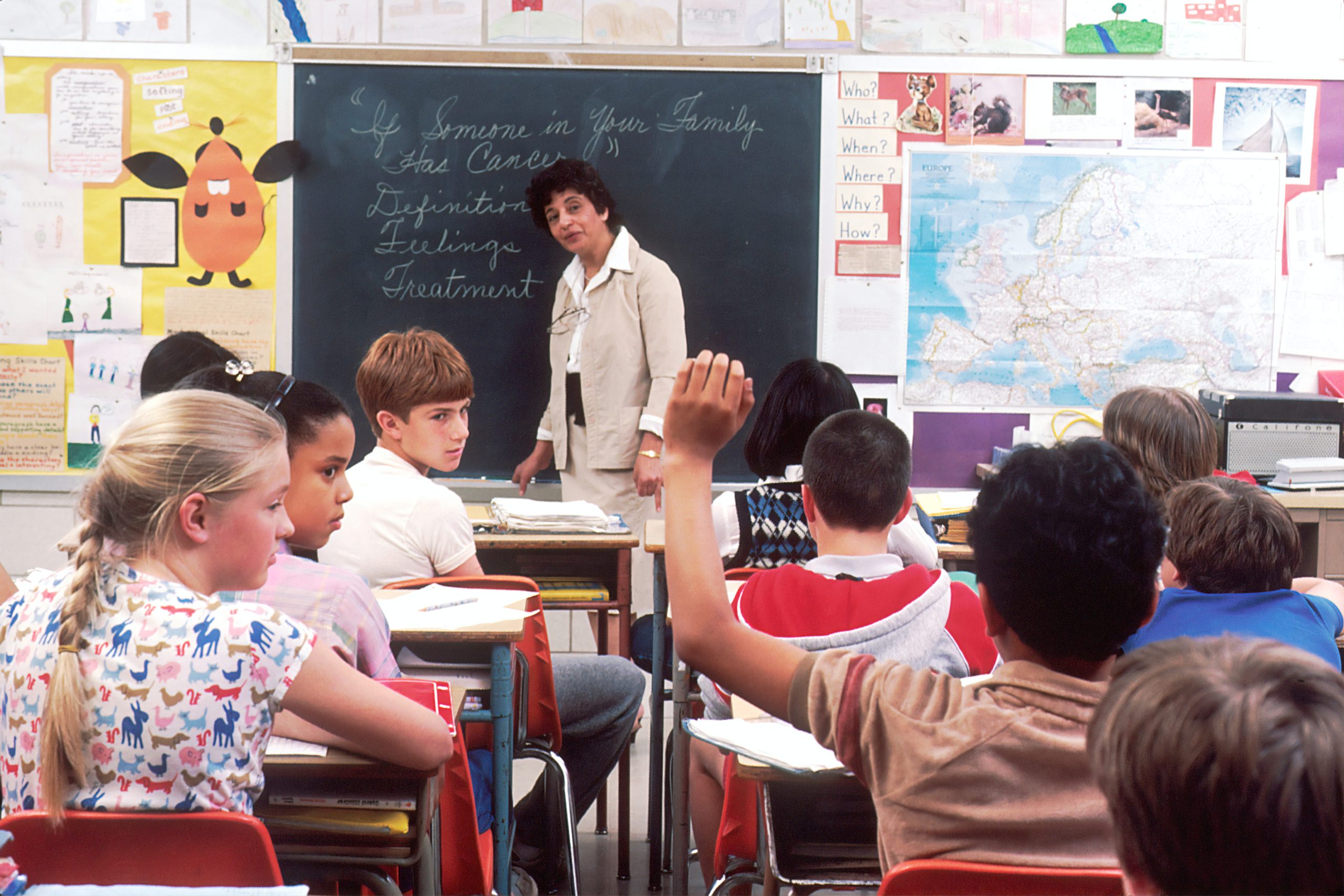

Title IX is a federal law prohibiting sex discrimination in education. It is one of the shortest laws on the books, with the operative provision stating: “No person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any education program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance.” Laws like this can be enforced in two ways: through the courts and through administrative agencies. Individuals have a right to bring lawsuits under Title IX in court, where it is the job of the court to interpret what the law means. In addition, federal agencies has enforcement powers to investigate and address violations of federal law. For Title IX, that agency enforcement power rests with the U.S. Department of Education and the U.S. Department of Justice. People whose right to be free from discrimination in education have been violated can file complaints with those agencies, which can then investigate the educational institutions and impose corrective action, including the withholding of federal funds. The U.S. Department of Education issues regulations interpreting the laws it enforces and explaining how it will apply those laws when it engages in enforcement action. In 2020 the first Trump administration issued regulations overhauling Title IX enforcement; in 2024 the Biden administration issued a new set of regulations that was immediately challenged in federal courts in various red states. CONTINUE READING ›

Since 2012, Massachusetts laws have prohibited discrimination based on gender identity, including in education. The Massachusetts Department of Education has had longstanding guidance in place instructing schools to use students’ preferred names and pronouns while at school. This week, in Foote v. Ludlow School Committee, the First Circuit Court of Appeals decided whether a school policy that followed this state law and DOE guidance violates parents’ constitutional right to direct the upbringing of their child. The school won. CONTINUE READING ›

Since 2012, Massachusetts laws have prohibited discrimination based on gender identity, including in education. The Massachusetts Department of Education has had longstanding guidance in place instructing schools to use students’ preferred names and pronouns while at school. This week, in Foote v. Ludlow School Committee, the First Circuit Court of Appeals decided whether a school policy that followed this state law and DOE guidance violates parents’ constitutional right to direct the upbringing of their child. The school won. CONTINUE READING › Boston Lawyer Blog

Boston Lawyer Blog