This week the Supreme Judicial Court (“SJC”) decided Commonwealth v. Newberry, in which it held that judges must arraign defendants prior to assigning them to pretrial diversion if the Commonwealth seeks arraignment. In my opinion the decision is wrong on the law, and eliminates an essential avenue for some defendants to avoid the negative consequences of a criminal charge on their records.

This week the Supreme Judicial Court (“SJC”) decided Commonwealth v. Newberry, in which it held that judges must arraign defendants prior to assigning them to pretrial diversion if the Commonwealth seeks arraignment. In my opinion the decision is wrong on the law, and eliminates an essential avenue for some defendants to avoid the negative consequences of a criminal charge on their records.

Under the law in question, the court may “at arraignment” delay the case for two weeks for assessment of the defendant’s suitability for diversion to a treatment or other program in lieu of prosecution. (The “program” in question can include community service, so diversion is a possibility even for those not in need of, for example, mental health or substance abuse treatment.) At the two-week return date, the court may, if it determines that the defendant is eligible for diversion, continue the case for 90 days to allow the defendant to complete the program, and then dismiss it following that period. The question in this case was whether the defendant must be arraigned before the case is diverted, if the Commonwealth so requests. Before the decision certainly many judges believed that they had authority to divert cases pre-arraignment even if the prosecution objected, and our office secured this disposition for a number of defendants. For example, in January 2019 I convinced a judge to grant a client pre-arraignment diversion on condition that he complete an anger management course and community service, over the objection of the Commonwealth.

This case will change the availability of that option. The SJC read the language in the statute stating that these events must take place “at arraignment” to mean that they cannot happen pre-arraignment if the prosecution objects. To my mind this reading is not at all mandated by the plain language of the statute. I would read the language “at arraignment” to indicate only that the determination should be made at the defendant’s first appearance before the court, i.e. their scheduled arraignment. The statute does not use language such as “after arraignment,” which would clearly indicate that defendants must actually be arraigned before diversion, or directly address whether diversion can take place prior to arraignment. And it nowhere gives the prosecution authority to stand in the way of diversion if the court finds it to be warranted, so it is bizarre that the court’s statutory reading gives prosecutors the discretion whether or not to demand arraignment in a particular case.

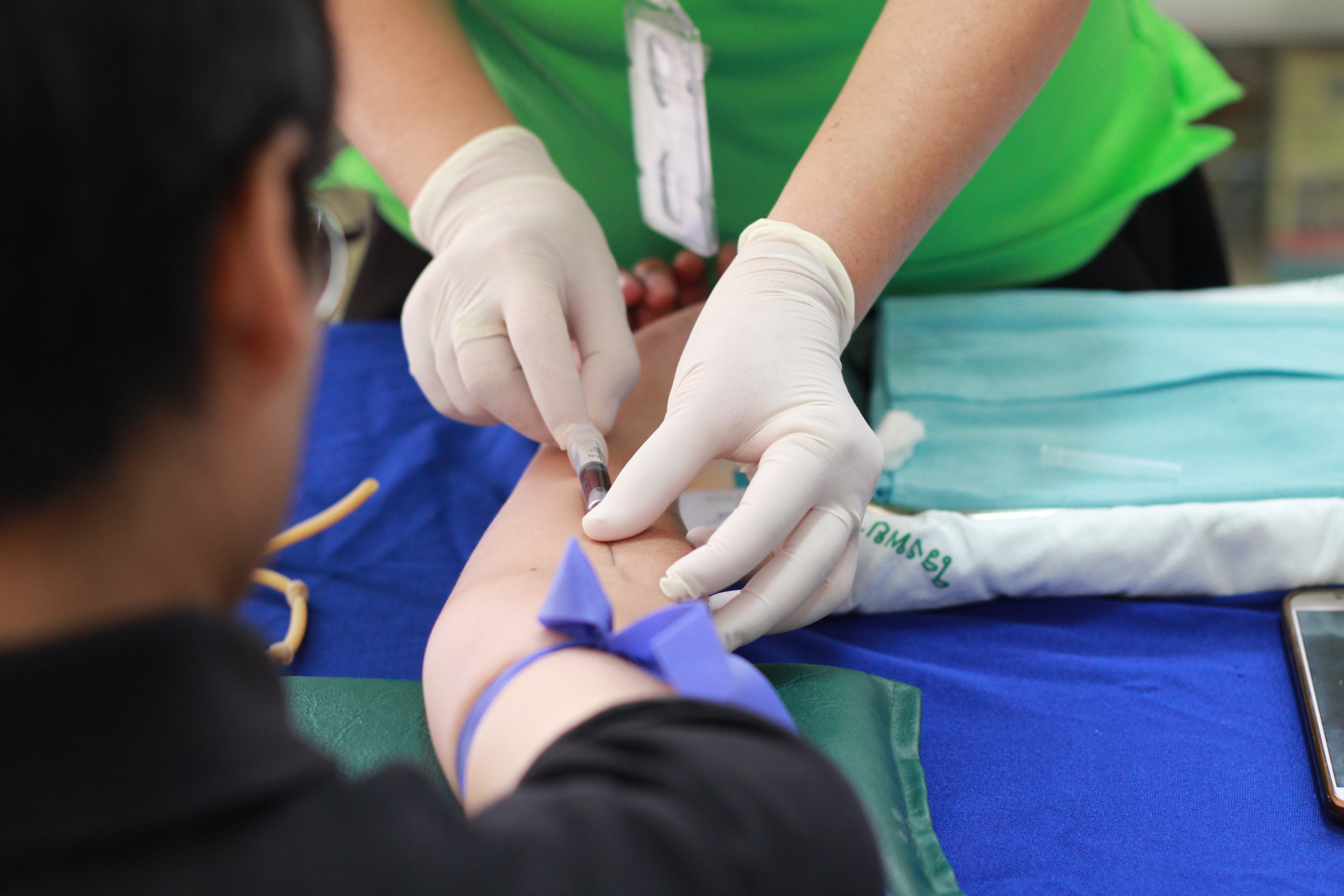

My colleague recently explained how Massachusetts and federal leave laws may apply to employees who contract COVID-19 or who are medically required to self-quarantine because of concerns about COVID-19. In addition to leave laws, such as the Massachusetts earned sick time law and the Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA), state and federal disability laws provide protections to employees. Disability laws also allow employers to require medical examinations and exclude employees from the workplace in certain circumstances.

My colleague recently explained how Massachusetts and federal leave laws may apply to employees who contract COVID-19 or who are medically required to self-quarantine because of concerns about COVID-19. In addition to leave laws, such as the Massachusetts earned sick time law and the Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA), state and federal disability laws provide protections to employees. Disability laws also allow employers to require medical examinations and exclude employees from the workplace in certain circumstances. Boston Lawyer Blog

Boston Lawyer Blog